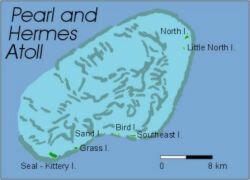

Pearl and Hermes Atoll is a true atoll that is primarily underwater and has numerous islets, seven of which are above sea level. While total land area is only 0.32 square kilometers (80 acres), the reef area is huge, over 770 square kilometers (194,000 acres). The atoll is ever changing, with islets emerging and subsiding.

The atoll is named after two English whaling ships, the Pearl and the Hermes, which wrecked on the reef during a storm in 1822. In 1854, King Kamehameha III claimed the atoll as part of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Since the atoll's land base is small, it was largely spared the ravages of guano miners and feather hunters. The atoll abounds with birds. Presently, about 160,000 birds from 22 species may be seen at Pearl and Hermes. They include black-footed albatrosses, Tristram's storm petrels, and one of two recorded Hawaiian nest sites of Little terns. The endangered Laysan Finch was introduced to the atoll in 1967 in an attempt to establish a "back-up" population.

The sandbar islets support coastal dry grasses, vines, and herbal plants, including 13 native species and 7 introduced species. The plants survive because they are salt-tolerant and able to recover from frequent flooding events.

Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles breed and feed at Pearl and Hermes, which is also a mating area for spinner dolphins. The atoll has the highest standing stock of fish and the highest number of fish species in the NWHI. These include saber squirrelfish, eels, Galapagos sharks, sandbar sharks, ulua (big jacks), angelfish, Ášweoweo (bigeye), uhu (parrotfish), and numerous lobsters. Hiding between the unique reef and lagoons are very unusual invertebrate habitats. Several sponges collected recently may be new to science!

Black-lipped pearl oysters, at one time very common, were harvested in the late 1920s to make buttons from their shells. Over-harvested, the oysters were nearly eliminated. Few oysters remain today, long after oyster harvesting was declared illegal in 1929.

While there has been less negative human impact on this atoll than others in the NWHI, problems with marine debris and the occasional shipwreck still occur. Continuing to minimize human contact may preserve the wildlife and marine life in this extensive reef ecosystem.

|